Engine-pedia: BMW’s legendary motorsport engines for the street

The era of high-revving, naturally aspirated M-car engines represents a golden age for BMW M and car enthusiasts alike. While the chassis are sharp and involving, the styling classically restrained but potent, it’s the sonorous naturally-aspirated engines that connect the M3 and M5 directly to the hearts of car enthusiasts.

Brutally expensive to buy, requiring intense maintenance, and intensely complex to get running, none of these engines are easy for engine swaps. However, if you’re set on having an engaging, brilliant naturally aspirated powerplant for your car, then these represent some of the best engines you could fit to a performance street car.

These 4, 6, 8, and 10-cylinder engines, often built by hand, share an obsession with individual throttle bodies, high compression, and soaring redlines, making them some of the most emotionally engaging engines ever produced. They are mechanical marvels that prioritize driver connection over forced induction.

Taking heed from Mercedes-Benz’s epic 300 SEL 6.3 by offering ballistic performance in a staid-looking sedan, the first BMW M5 (E28) was a revelation when it launched. It wasn’t brash like a muscle car, but this wasn’t your grandpa’s stodgy old BMW sedan either.

The heart of the first M5 was a 210kW (286hp) DOHC 3.6-litre in-line six-cylinder coded M88/3. This was an evolution of the M88 engines from the M1 supercar and a distant relative of the M49 from the E9 CSL. The E28 M5 effectively birthed the whole super-sedan market, with its high-revving nature and glorious sound track provided by the (at the time) unique individual throttle-body intake manifold, and it shared these mechanicals with the E24 M635CSi that won countless races around the globe.

For the follow-up E34 M5 the engine was evolved and renamed into the S38B36. It was boosted to 3.6L (S38B36, 311hp or 232kW), and then to 3.8L (S38B38, 336hp or 250kW), adding sophistication like variable-length intake runners (a precursor to VANOS) on the later 3.6L and higher-compression plus advanced coil-on-plug ignition on the 3.8L unit.

The motorsport roots of the S38 show their colours with the engine’s ferocious need for maintenance, particularly with regard to valve clearances. These require manual adjustment of the shim-and-bucket set-up, though the whole engine is highly sensitive to neglect. Timing chain tensioners and oil spray bars on early engines can be trouble spots, while the complexity of the Motronic 3.3 electrical system on the 3.8L variant can be challenging to diagnose today.

None of this matters for enthusiasts who hear the S38’s siren song. The sound is metallic, raw, and magnificent and, as the last of the hand-built M engines, the S38 is revered for its classic, analogue feel. The success of the S38 led directly to one of the most legendary powerplants of the Group A era.

When BMW switched their racing programme from the heavy E34 6-series platform down to the new, lightweight E30 3-series they created a legend with the first M3. The S14 is arguably the most racing-focused engine of the group but it was basically created by taking the M88/S38 inline-six and cutting off two cylinders.

The S14 was built purely for Group A Touring Car racing homologation, as the heart of the original M3. Its short stroke and incredibly low reciprocating mass allow it to rev with hyper-responsiveness, and the high-flowing DOHC cylinder head and ITB intake means it sounds like a pure race car.

Launched originally as a 2.3-litre in-line four, and later upgraded to a 2.5-litre, it had all the fruit to build into a successful Group A motorsport engine: 235hp (175kW) of power, 10.5:1 compression, a rugged iron block, forged reciprocating internals, low 140kg weight, and it revved to 7250rpm in production car form (over 9500rpm in the race variants).

As with the M88 and S38 the S14 is an expensive engine to own with a voracious appetite for maintenance. The high-RPM nature of these engines leads in many cases to accelerated wear on bearings and valvetrain components, which all cost serious money thanks to the higher levels of engineering involved in these bespoke motorsport-oriented engines.

However, as BMW entered the 90s they switched away from homologation specials to imbibing their M car engines with better road car-engineering while maintaining the motorsport feel. The E36 M3 moved to the 3.0-litre (later 3.2-litre) S50 six-cylinder, based off the then-new M50-series DOHC architecture.

While the S50B30 and S50B32 wowed enthusiasts, the S54B32 found in the E46 M3 is still regarded as one of the greatest naturally aspirated powerplants found in production cars, even to this day. This DOHC, all-aluminium 3.2-litre six produced 338hp (252kW) which is an astounding 103hp-per-litre - the highest horsepower-per-litre of any mass-produced naturally-aspirated six-cylinder engine at that time.

The final and most advanced naturally aspirated I6 engine from BMW M Sport, the S54 introduced electronic throttle control and the famous Double-VANOS system, offering variable valve timing on both intake and exhaust, for massive torque spread. It holds the highest specific output (103hp/L or 76.8kW/L) of any mass-produced naturally aspirated six-cylinder engine at its launch.

Rod bearing failure is the most infamous issue, often attributed to tight factory clearances and improper oil grade, though this issue can be solved with high-quality aftermarket bearings. The hub and oil pump disk bolts in the VANOS assembly are also common and expensive failure points, but these aren’t terminal issues for such a highly wound engine.

The S54 is widely considered the best-sounding and most balanced M-car engine ever made, with its linear power delivery, glorious intake noise, and 8,000RPM redline, to deliver a phenomenal driving experience. It contrasted brilliantly with the E39 M5’s character, which was on sale at the same time.

Today a well-maintained manual-equipped E46 M3 remains a visceral, engaging car to drive and this engine represents the ultimate I6 to swap into other BMW chassis, particularly the lightweight E30 as that model’s 6-cylinder M20 engine was an outdated SOHC design making a paltry 125kW.

For the first time the M5 had moved to a V8, a 400hp (299kW) five-litre unit coded S62B50. Unlike previous M engines, the S62 was developed from the M62 V8; a standard production V8 block found in regular 5- and 7-series cars. The S62 received extensive M-division upgrades, including a cast aluminium block, forged crankshaft, and individual throttle bodies for the first time on a V8, and it brought immense torque to the M5 platform.

Weak points involve VANOS pressure lines which can fail, leading to oil leaks, and timing chain guides which wear quickly. The non-return valves in the VANOS system can fail, causing startup rattle. The throttle position sensors (TPS) on the ITBs can also fail.

The perfect balance of high torque and high revs (for a V8). The E39 M5's stealthy looks combined with the powerful V8, created a cult classic. Its legendary reliability (relative to its successors) makes it highly desirable.

For the follow-up E60 M5 BMW took a hard left turn, with design and engineering. Available solely with an SMG transmission rather than a conventional manual gearbox and featuring controversial Chris Bangle-led design, the E60 represented a huge shift in the thinking a M Sport. And it was powered by one of BMW’s greatest, most-misunderstood engines: the S85B50.

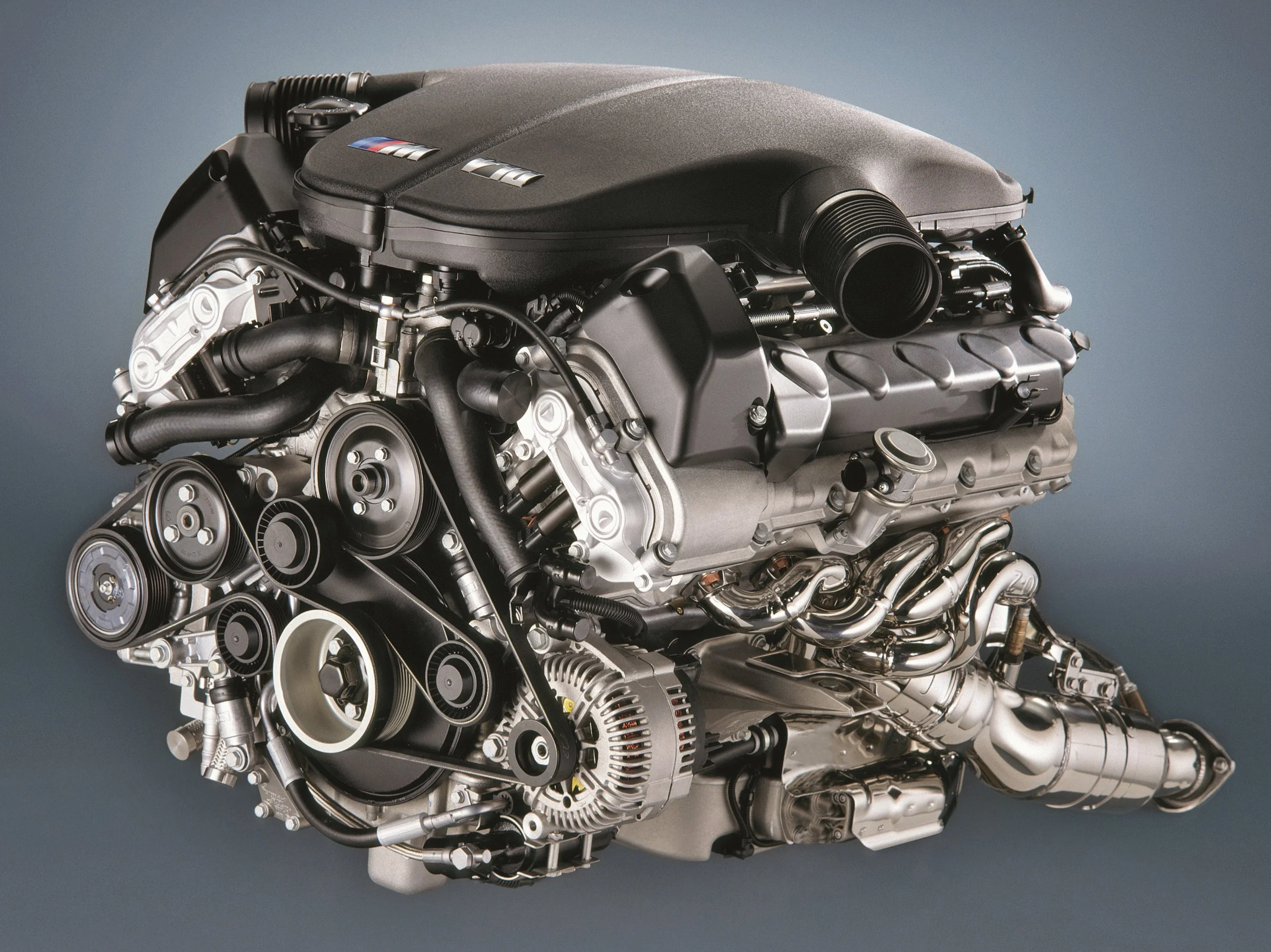

Directly inspired by BMW's Formula 1 engine program in the early 2000s as well as a stillborn Le Mans class based around V10 engines, the S85B50 is a bespoke, high-tech, and incredibly exotic design which ran solely in the E60 M5 (and associated M6). It features a 90-degree angle, 505hp (373kW), ten individual throttle bodies, and an 8,250RPM redline, and it was the first and only V10 ever put in a production BMW.

Packing such a high power output and RPM capabilities into just five-litres of capacity places incredible stresses on internal components. Rod bearing failure is the most notorious and potentially catastrophic issue with the S85, while VANOS pump failures (due to a high-pressure line) and the subsequent failure of the VANOS solenoid packs are extremely costly. Throttle actuators also fail regularly, though the S85’s intensive complexity translates to high maintenance costs.

A truly special, high-strung, and dramatic engine, the S85’s V10 howl is unmistakable and one of the best exhaust notes in automotive history. It represents BMW's maximum effort in naturally aspirated performance.

For the E9x-platform M3, which debuted at the same time as the E60 M5, BMW decided to work smarter not harder. They cut two cylinders off the storied V10 to create the S65B40; a 414hp (309kW) four-litre DOHC V8 which boasted an 8400rpm redline.

With an aluminium block, eight individual throttle bodies, 12:1 compression ratio, and a low center of gravity, the S65 represents the final naturally aspirated M3 engine, and the final NA M Sport engine from this classic lineage. It also had the highest specific output of any production BMW V8.

The shared base of the S85 means rod bearing failure is a persistent and significant issue, as are throttle actuators which have become common failure points as the plastic gears wear out, and the oil cooler lines can degrade.

However, the S65’s Formula 1-esque shriek, entirely unique for a road-going V8, makes it a beloved engine among enthusiasts. It's renowned for its immediate throttle response and high 8,400RPM redline, and it represents the final and most powerful naturally aspirated M3 engine.